Shaping Dough With No Proofing Basket

Next in my explorations, I turned my attention to baking a boule without using a proofing basket or banneton for the final dough proving. In some ways a banneton makes shaping the loaf easier, but it does introduce some risk to the process. It can be tricky to transfer the loaf from the banneton to the baking pan or pot. Sometimes, the loaf deflates when it lands, especially if it has stuck to the basket in some way. Plus, how many people have bannetons in their kitchens — though they are inexpensive and easy to find online.

I decided I would test hand shaping for both my simple autolysed/kneaded loaf described earlier and another loaf to which I added two stretch and fold sessions also described above.

The Autolysed/Kneaded Bread

The simple autolysed/keaded dough was allowed to proof for about two hours and when it was ready to be shaped, I scraped the dough out of the bowl onto my floured surface. To form a bread loaf, I folded it into a ball, as with my other experiments, by taking sections of dough and folding them to the center until the dough was roughly spherical.  But instead of placing it in a banneton, I created surface tension on the top dough surface by tightening the dough.

But instead of placing it in a banneton, I created surface tension on the top dough surface by tightening the dough.

I held the dough in both my hands with the top—smooth side—up and the gathered side down. Then with my hands, I began to gently pull the top surface dough underneath. This surface tightness acts much like the rubber membrane of a balloon that stays intact and expands with air as the bread bakes. I was hoping to get better oven spring, which is the additional rising that occurs from the heat of the oven. And with this method, I could let the dough ball do its final rise right on my baking pan, (on parchment paper or a dusting of cornmeal) so it could remain undisturbed while placing the pan in the oven to bake. This was a distinct advantage.

I was so surprised by the result. Creating that surface tension made a big difference. The oven spring added much more height and openness to the bread. I was delighted. The recipe for how to make this simple boule is on my Domestic Bliss blog.

Adding Stretch and Fold Steps

When I used this method of hand shaping on the recipe that adds two stretch and fold sessions, it also came out higher than the comparable loaf that proofed in a banneton. It maintained its shape very well and gained even more height in the oven. The recipe for how to make this classic boule is on my Domestic Bliss blog.

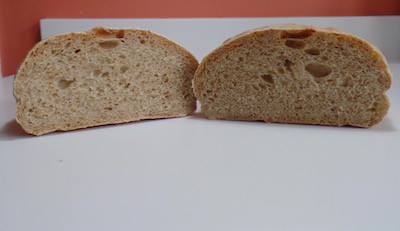

Below shows the two hand shaped loaves that were given the surface tension treatment side by side on a counter. The loaf on the right was autolysed and kneaded. The loaf on the left started out the same way, but underwent two stretch and fold sessions during the proofing. It held its height better, but was a little more inconvenient. Both were absolutely delicious.

Does Surface Tightening Work For Wetter Dough?

So this dough tightening to increase the surface strength and tension is a valuable technique to learn and practice. It’s not too difficult to learn, especially if the dough isn’t too wet. With stickier dough, it’s a little harder to do.

I made sourdough bread this way, which generally needs to be a pretty sticky dough in order to form those signature holes in the loaf. I found I could shape and tighten the loaf this way by using a little more flour on the dough and on my hands when I was forming the loaf. It baked up with good oven spring and was moist and holey without using a covered pan like a dutch oven. I didn’t have to transfer the fully proofed loaf to another pot. It did its final rise on a baking pan which I carried over to the oven and placed inside.

This wraps up my explorations into making great bread easily and conveniently through the enhancing of natural gluten formation. I think my results speak for themselves in the photographs of my lovely loaves. You can make these loaves yourself by watching the two instructional videos I made. How To Make A Simple Boule will show how to make a very good loaf in the most convenient and flexible way. Classic Country Boule adds the two stretch and fold turnings that make this loaf rise even higher. I hope you will try them to enjoy these delicious treats.

Next I’ll be onto enhancing the fermentation process. So check back again to follow my experiments on this second major process of bread making.

Click to Subscribe to this Blog.

Learn More About the Dome Dough Maker

High Hydration Dough

High Hydration Dough Boules are a great loaf shape to test because dough has a tendency to spread and flatten out with gravity, so you want strong dough with enough elasticity to keep a shape. Loaves that are baked in pans are constrained to maintain their shapes, so it’s harder to tell whether they have that strength. So what I’m really testing with my boule making is whether the protein architecture is making an elastic dough with enough dough strength to hold together, hold a shape, and hold in air. This architecture of the dough is built by gluten and it’s been helpful to know how gluten forms.

The second process — fermentation — called proofing bread or proving bread happens when starches in the flour are consumed by yeast and bacteria. Fermentation provides the gases that fill the elastic gluten architecture and raise the dough’s volume. You need both systems to make bread. And we can use methods that optimize these two processes to more easily turn out great results. In this post, I’m going to focus on gluten formation. I’ll post about the yeast fermentation process in a future post.

Boules are a great loaf shape to test because dough has a tendency to spread and flatten out with gravity, so you want strong dough with enough elasticity to keep a shape. Loaves that are baked in pans are constrained to maintain their shapes, so it’s harder to tell whether they have that strength. So what I’m really testing with my boule making is whether the protein architecture is making an elastic dough with enough dough strength to hold together, hold a shape, and hold in air. This architecture of the dough is built by gluten and it’s been helpful to know how gluten forms.

The second process — fermentation — called proofing bread or proving bread happens when starches in the flour are consumed by yeast and bacteria. Fermentation provides the gases that fill the elastic gluten architecture and raise the dough’s volume. You need both systems to make bread. And we can use methods that optimize these two processes to more easily turn out great results. In this post, I’m going to focus on gluten formation. I’ll post about the yeast fermentation process in a future post. But you can have too much strength and make the dough too elastic, having too much ability to snap back and not enough ability to stretch. This ability to stretch is called dough extensibility. When you’re stretching out pizza dough, extensibility is a must.

But you can have too much strength and make the dough too elastic, having too much ability to snap back and not enough ability to stretch. This ability to stretch is called dough extensibility. When you’re stretching out pizza dough, extensibility is a must. A higher water content — higher than what was traditionally used — does make hand kneading more difficult, because wetter dough is sticky dough and it gets stuck to surfaces and is kind of messy. You can be tempted to add more flour to be able to hand knead at all, which defeats the purpose. Compare the results of these two boules I baked. The one on the bottom was hand kneaded for 10 minutes, but in order to do it, I had to add a couple of tablespoons of flour, so it didn’t rise as well as the bread on the top which was kneaded with the dome for one minute.

A higher water content — higher than what was traditionally used — does make hand kneading more difficult, because wetter dough is sticky dough and it gets stuck to surfaces and is kind of messy. You can be tempted to add more flour to be able to hand knead at all, which defeats the purpose. Compare the results of these two boules I baked. The one on the bottom was hand kneaded for 10 minutes, but in order to do it, I had to add a couple of tablespoons of flour, so it didn’t rise as well as the bread on the top which was kneaded with the dome for one minute.

This gives the proteins time to fully unlock and knit together with many cross links before stretching and aligning them.

This gives the proteins time to fully unlock and knit together with many cross links before stretching and aligning them.

Using a banneton basket helps to mold the bread into a polished looking loaf.

Using a banneton basket helps to mold the bread into a polished looking loaf.  After the kneading step, I let the dough proof for 45 minutes, then did one stretch and fold session. I allowed it to proof another 30 minutes, then did a second stretch and fold session. Stretching and folding does de-gas the dough so I let it recover volume for 45 minutes before placing the dough in a banneton. Altogether, this was two hours of proofing before placing it in the banneton – the same amount as my test with the autolysed/kneaded dough. What was the result? Yes, adding stretching and folding did make a difference in dough strength and dough height. It held its shape better once dispensed from the banneton and baked up higher.

After the kneading step, I let the dough proof for 45 minutes, then did one stretch and fold session. I allowed it to proof another 30 minutes, then did a second stretch and fold session. Stretching and folding does de-gas the dough so I let it recover volume for 45 minutes before placing the dough in a banneton. Altogether, this was two hours of proofing before placing it in the banneton – the same amount as my test with the autolysed/kneaded dough. What was the result? Yes, adding stretching and folding did make a difference in dough strength and dough height. It held its shape better once dispensed from the banneton and baked up higher.

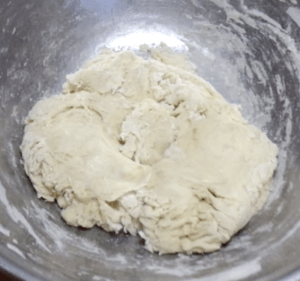

When I checked the dough after about an hour, it had risen, but looked different than kneaded dough. Its surface was more perforated with air holes than kneaded dough, as if the dough didn’t have the tensile strength to hold in the air. The picture to the left shows how it looked after two hours. I placed it in a banneton for the final rise. When I dispensed the dough from the banneton, there was a real difference. It stuck a little bit to the banneton. It spread out more on the baking sheet and lost height. It didn’t have the elasticity of kneaded bread. Nevertheless, it was still good to eat. Homemade bread is so very forgiving, as long as it isn’t dense and dry.

When I checked the dough after about an hour, it had risen, but looked different than kneaded dough. Its surface was more perforated with air holes than kneaded dough, as if the dough didn’t have the tensile strength to hold in the air. The picture to the left shows how it looked after two hours. I placed it in a banneton for the final rise. When I dispensed the dough from the banneton, there was a real difference. It stuck a little bit to the banneton. It spread out more on the baking sheet and lost height. It didn’t have the elasticity of kneaded bread. Nevertheless, it was still good to eat. Homemade bread is so very forgiving, as long as it isn’t dense and dry.